Cancer Care

Want to learn more about this at Kettering Health?

Ask Brittany Carnahan about her story, and she’ll start with two memories.

The first takes her to a loud living room in Centerville, Ohio, on January 22, 1989. A five-year-old Brittany watches her mom and aunt hurl amateur coaching calls at the TV as they watch the Cincinnati Bengals play the San Francisco 49ers in Super Bowl XXIII. “I can still see them yelling,” Brittany recalled. “That’s where I learned to yell during games, especially ‘Who Dey.’”

The second sends her to a quiet recovery room at Kettering Health Main Campus on September 12, 2014. With the fog of anesthesia lifted, Brittany learns with her husband, Mike, that the tumor in her back is not benign. It’s a rare and aggressive cancer, typically found in children—not 31-year-old women. And it’s wrapped around her lower spine.

“I had no words.”

Look for the Bengals scrub cap

Years before she was a patient, Brittany was a nurse. She began her career at Kettering Health Main Campus in 2003, first as a nursing assistant, then as a registered nurse in medical-surgical nursing. In 2011, she moved to radiology to care for cancer patients.

Brittany describes herself as “thickheaded and softhearted,” traits she says she comes by honestly as a lifelong football fan. She speaks candidly, like a trusted neighbor with tough news, to patients and colleagues alike. Much of her day involves thinking about or discovering difficult details—lab and imaging results, biopsy results, etc.—working only steps away from patients’ hopes, fears, and dreams. Speaking to patients candidly, then, is an act of compassion. And a soft smile or a comforting chuckle is normally not too far behind, when appropriate. For her colleagues, she reserves well-aimed jabs of sarcasm—especially for those who, in her words, aren’t Bengals fans.

Along with wearing her heart on her sleeve, she developed a reputation for wearing as much orange and black as she could.

If a patient or colleague needed to find Brittany, all they had to do was look for her Bengals scrub cap. But if they couldn’t find her cap, they could find her by looking for the radiology nurse limping from patient to patient.

In 2006, Brittany began to wrestle with back pain. On bad days, it felt like a vice grip clamped down on her lower back. But she learned to live with the pain, which seemed about as stubborn as she was. “It’s fine, it’s fine,” she’d affirm to anyone who asked if she were OK.

Over the next five years, Brittany had three surgeries, her appendix and gallbladder removed, numerous tests, physical therapy, and bouts of medication regimes—with no relief. In her view, the pain came down to a professional hazard. “I lived on my feet 10-12 hours a day,” Brittany said. “That’s the nurse’s life, right?” So each day, Brittany gritted through the pain, focusing on caring for patients and raising Alexis, her daughter—and, during football season, cheering for the Bengals.

As far as her back pain was concerned, Brittany had no interest in any more tests or scans.

A lifesaving phone call

In August 2014, she limped away from assisting with a procedure and learned that a radiologist and close friend—Dr. Joseph Blake—called Brittany’s doctor to schedule an MRI for her. For months, Dr. Blake had seen her limp throughout her days and pass the pain off as nothing.

“I know you’re tough,” he’d say to her, “but . . .”

“Oh,” Brittany would interject, “It’s just sciatic pain. It’s a pinched nerve.”

But she knew, along with Dr. Blake, that she was “saying everything I could think of to say nothing was wrong with me.”

Within 30 minutes, Brittany was enveloped in the punctuated mechanical hum of an MRI scanner. Dr. Blake monitored. After hopping off the scanner, Brittany joined him to review the scans. “I remember hearing him scrolling his mouse,” Brittany recalled.

“‘Hello? Hello?’” Brittany asked, waiting for him to turn from the scans with good news.

“Let’s see who’s reading neuro today,” Dr. Blake said.

“Oh boy,” Brittany thought.

Brittany’s MRI revealed a tumor in her lower back. Based on her symptoms, it was anticipated to be benign.

Two weeks later, Brittany had surgery at Kettering Health Main Campus, an L-5 laminectomy with tumor debulking, to remove as much of the tumor as possible and to have it biopsied. Brittany remained optimistic. She saw this as a quick fix for the belabored tug-of-war with her lower back. As she awoke in the recovery room, wiggling her toes and fingers, she held onto the expectation for good news with white knuckles. But even her Midwestern optimism buckled under the weight of the biopsy results and the words “primitive neuro-ectodermal tumor,” or PNET.

Rare pediatric tumors, PNETs are considered Grade IV, which means they’re cancerous and fast-growing. They normally grow in the brain, developing from primitive (undeveloped) nerve cells. And they come with less-than-hopeful survival odds; the five-year survival rate doesn’t exceed 35%.

Brittany’s tumor was especially rare. Not only was she well-beyond the normal age to have such a tumor, but her scans showed the tumor had grown only around her spine. To verify, a sample was sent to and confirmed by experts at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Thinking back on Dr. Blake’s deciding to call and schedule the MRI, Brittany shared, “He saved my life with that phone call. I wouldn’t be here if he hadn’t done that.”

Dry eyes, a flat look, and “the wrong woman”

Brittany recovered from her surgery for the next five days. Mike and her mom alternated staying the night with her. Both noticed that after nurses and specialists and friends left each day, Brittany maintained what her mom described as a “flat look.” Hoping to help Brittany process, they reminded her, “You can cry. You haven’t shed a tear.” But Brittany wasn’t waiting for a trusted audience before she cried. Instead, Brittany devoted her emotional stamina to making sense of the view from her patient bed.

“I was in a state of shock,” shared Brittany. “I’ve worked with patients from biopsy to port placement. Now, I’m on this side of it.”

She thought she knew the territory of the patient bedside. But now, she was a stranger in a foreign land. The beeping vitals on the surrounding monitors were hers. The food delivered to the room was for her. She saw her name, not on her nurse’s badge, but at the top of the whiteboard across the room.

About a month and a half after recovering from surgery, Brittany prepared for chemo and radiation treatment. She and Mike met with her oncologist, Dr. Alejandro Calvo, who explained the course of treatment and wanted to prepare them for the possibility that Brittany “might not return to doing everything like before.” To which Mike, her high-school sweetheart, quickly interjected:

“You just told that to the wrong woman.”

Brittany’s course of treatment would be rigorous: chemo on Mondays (eight hours), Tuesdays (four hours), and Wednesdays (seven hours)—every four to five weeks—along with 35 radiation treatments Monday through Friday, focused on her spine.

But before her treatment began, Brittany’s family knew one thing would steal her nerves, encourage her heart, and prepare her mind: a Bengals game.

“I live for the football season,” said Brittany. “And I knew the Bengals would get me through treatment.”

A fight on two fronts

Brittany began treatment at Kettering Health Cancer Center on November 4, 2014. Bengals-inspired get-well baskets from friends and colleagues soon filled her front porch and the treatment bays she sat in. For anyone who wanted to find Brittany in the Cancer Center, all they had to do was follow the sound of Brittany reading Bengals stats aloud to her dad, her “chemo buddy,” from underneath her Bengals quilt.

Oftentimes, patients undergoing chemotherapy experience a side effect called peripheral neuropathy, which may lead to a heightened sensitivity to the cold. Patients, then, typically wear sweaters and thick winter hats and use lots of blankets. These sweaters, hats, and blankets often take on the symbolic weight of the rigors of treatment, becoming tangible reminders of the long days patients go through to try to do to cancer what cancer had been doing to them.

For Brittany, her Bengals quilt, handmade by friends, became more than a way to stave off the cold. It became a shield, to guard her soul against the invisible toll cancer takes on a person. “I would drape that around me during treatment,” shared Brittany. “It kept me upbeat, giving me something hopeful to focus on.”

And while the chemo entered her body to fight cancer at the cellular level, Brittany mounted her own fight at the emotional level. She mustered strength from beyond the world of the cell, where the human compulsion to be part of something bigger and the human capacity to hope for something more resides. A place veiled to microscopes and MRIs but visible on the faces of fans desperately believing their team can accomplish the impossible and on the faces of patients courageously pushing their bodies toward remission.

As an experienced radiology nurse, Brittany knew the ins and outs of cancer treatment. And as a Bengals fan, she felt she had a story that helped her navigate cancer treatment. “Watching the Bengals for so many years, seeing their determination each season, watching them make tough changes and do hard things, it made me realize I can do anything, as long as I have the right people behind me,” said Brittany.

“For me, it was my family and my doctors. For the Bengals, it was their coaches, their teammates, and their fans.”

In other words, as Brittany emphasized, “The Bengals got me through it.”

Two words

Brittany’s treatment ended in late January 2015, just in time for her to watch the rest of the playoffs from home. Recovering at home proved difficult, though. Her family found their warnings regularly ignored as they reminded Brittany to “slow your roll” as she tried to get back to work. And while her stubbornness was a sign of her vitality returning, she’d need to wait before donning her Bengals scrub cap again.

In 2016, Brittany returned to Kettering Health, joining the radiology staff at Soin Medical Center.

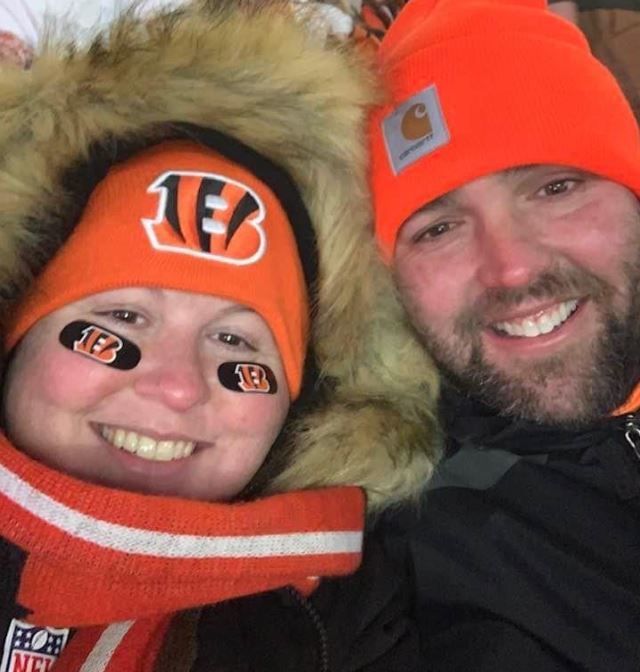

Along with returning to work, Brittany made sure to return to another place she felt she belonged: Bengals games. Among the many games she and Mike attended since 2016, they went to two Crucial Catch games, in 2020 and recently in 2022, as well as the all-important wild card game where the Bengals defeated the Las Vegas Raiders, ending their 31-year playoff drought.

And in 2021, after six years of routine scans, Brittany was told by Dr. Calvo that all she needed to do was manage any lingering symptoms from her treatment. Brittany was in remission.

In many ways, Brittany is still the same “Bengals-gear wearing nurse” she’s always been—with her Bengals scrub cap, Bengals earrings, orange and black tennis shoes, and shimmering Bengals phone case (which she received for free because she bought so much Bengals Super Bowl apparel).

But she’s different, too. “Being a nurse now, knowing what I know about being a patient,” Brittany shared, “I’m a better nurse a million times over.” And she doesn’t walk with a limp.

Today, it’s easy to find Brittany in the halls of Soin Medical Center. Just look for the Bengals scrub cap. Or, follow the sound of Brittany chanting two words—year-round—that she learned from her mom, two words that “send chills down my spine.” Because for Brittany, they’re more than a chant. They’re her story.

Who Dey.