Women’s Health

Want to learn more about this at Kettering Health?

When Dr. Kelly McCluskey-Erskine, OB-GYN, talks with patients experiencing postpartum depression, her words come from the heart.

She’s been there.

Now an OB-GYN with Kettering Health, Dr. McCluskey-Erskine had just finished her first year of medical school when she gave birth to her first child. The pregnancy and delivery went well, but life with her newborn began far from the picture-perfect experience she imagined.

“You have this idea in your head of what a good mom does: ‘I should have this beautiful vaginal delivery, and then I can take home my baby, whom I will love unconditionally and never be frustrated with, and then I will breastfeed my baby and everything will be wonderful, and we’ll be this happy family unit,’” she says.

But in reality, “For me, it was a lot of middle-of-the-night crying. A lot of resentment toward my child—feeling trapped and stuck.”

Isolation and self-doubt

Dr. McCluskey-Erskine recalls how her medical school friends were focused on starting their clinical rotations. “And here I was with this baby, so I was feeling very alone,” Dr. McCluskey-Erskine says.

The struggle to breastfeed intensified her isolation. “I felt like I couldn’t go anywhere because breastfeeding was so difficult that going into public was difficult. Taking the time to get the baby to latch for a new mom can be difficult and doing so in public can be more stressful. I was resentful of my husband because he couldn’t feed the baby, either.”

Dr. McCluskey-Erskine lived under that cloud of frustration and resentment for about a month before she realized she was suffering from postpartum depression. “The first couple of weeks, I played it off as being hard just because being a parent is hard. But after that it was more like, ‘OK, this should be getting better, right?’ And it just wasn’t.”

Reassurance and empowerment

Though compared to some women’s depression, Dr. McCluskey-Erskine’s “wasn’t particularly terrible—there were no suicidal thoughts, and I did not ultimately require medication”—the worst of it still lasted about three months.

Talking with her doctor and attending joint counseling with her husband helped, “but I felt like I shouldn’t have had these problems because I should know better,” she says. “I’m in medicine—even though I wasn’t a physician yet, I still felt like I should have been knowledgeable enough to avoid this kind of situation and that it was something I could have controlled.”

Reassurance finally came—in one of her second-year classes. “In the gynecology portion, we talked a lot about postpartum depression and how it happens—but also that women don’t talk about it to one another,” she says. “We always want to post our fancy, happy pictures of our families, and everybody is supposed to be super happy and feel wonderful about the situation, and we feel like we can’t project any other view of parenthood.

“So knowing that I wasn’t the only person who felt that way was really important,” she continues. “Nobody had ever talked to me about it. Nobody in my personal life, or family or friends, had ever said, ‘Hey, this was a problem for me. Are you having any issues with that?’”

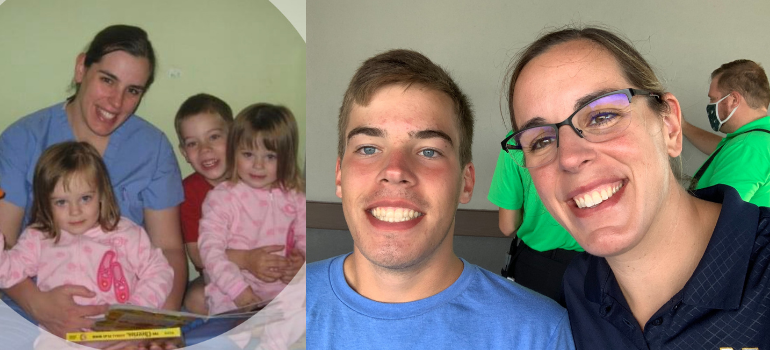

With greater awareness of postpartum depression and her risk of it, Dr. McCluskey made sure she had more resources in place for her second pregnancy. When her twin daughters were born, “we were more prepared,” she says. “Although I did have some sadness, I was able to recognize it sooner and get resources in place—like getting good sleep and making sure I had help.”

Reaching out to patients

In the years since her son was born, she has been glad to see the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and its members take strides to improve awareness, intervention, and treatment of postpartum depression.

“It’s been almost 18 years, so we’re doing a much better job of bringing it up—talking about it while patients are pregnant and screening for it at their postpartum visits,” she says.

Having experienced postpartum depression firsthand, Dr. McCluskey-Erskine brings that perspective with her when interacting with her own patients.

“They may not even realize themselves what their problem is,” she says. “A lot of them feel very alone. A lot of them feel like, ‘this couldn’t possibly happen to anybody who knows what they’re doing, and I’m a bad mom.’”

Even doctors are susceptible to postpartum depression, and learning that normalizes it somewhat for patients when they realize “it can happen to anyone, even if you’re prepared for it, even if you know it can come, even if you have support,” she says.

Sharing her personal experience helps patients “feel that they can relate to me and really open up about what is actually happening and the thoughts that they’re having.”

Warning signs

Dr. McCluskey-Erskine says that it’s normal in the first couple of weeks to feel a little ‘off’ while your hormones are changing, and there are a lot of things going on in your body.

“But if you’re feeling that you are inadequate all the time, or that you don’t want to get out of bed, or that you don’t want to take care of yourself, or that you are not attached to the baby like you don’t feel the need to go get the baby when it cries—if you think to yourself, ‘they would be better off if I had left them here’—those kinds of things—patients should know that they can talk to us about that,” she says.

“We’re not necessarily going to put everybody on medication, and we don’t think that they’re crazy,” she continues. “We are really just there to help them and walk them through that.”

Spouses and partners can also keep an eye out for symptoms. “I’ve had partners call and tell me that they are concerned about their wives or their girlfriends. Sometimes the partner is the best litmus test for how they’re feeling.”

Help is available

If you think you or someone you know might have postpartum depression, the first step is talking to your obstetrician. “For any patient, the goal first and foremost is to get them into the office to be seen,” Dr. McCluskey-Erskine says.

Be honest with your provider about how you’ve been feeling. From there, she or he can advise you on treatment options and the best course of action for your circumstances, as well as refer you to other professionals and resources as appropriate.

“Counseling is always my first recommendation for anybody who comes in with depression,” she says. “The Dayton area has a good number of counselors, including some who specialize in postpartum depression or have a special interest in it.”

She also recommends a support group, POEM (Perinatal Outreach & Encouragement for Moms), the Ohio chapter of Postpartum Support International. The group currently meets virtually and provides other resources.

“I just want them to know that there are so many women who suffer from postpartum depression and postpartum anxiety,” Dr. McCluskey-Erskine says. “And that although it’s not ‘normal,’ it is very common, and there are many people out there willing to support them and help them find resources—but they have to come forward and talk to us.”