Emergency and Trauma Care

Want to learn more about this at Kettering Health?

On the fifth floor of Fort Hamilton Hospital, around 1:30 p.m., Surgeon Dr. Andrew Lichter finishes his rounds. At 32 years old, Dr. Lichter is an eager attending physician, practicing general surgery, including advanced surgical robotics, breast surgery, and trauma care.

He talks with a patient, taking advantage of the slower Sunday pace.

An announcement fills the halls: “Category 1 trauma. Here now.” Dr. Lichter turns toward the stairs. The designation “category 1” means a patient has arrived in the midst of the “golden hour,” the 60-minute window trauma surgeons have to save a patient’s limb or life.

Dr. Lichter hurries toward the trauma bay on the first floor. But he doesn’t run. He doesn’t want his hands to shake.

“Running gets your heart rate up,” said Dr. Lichter. “I use that time, that minute or two, to collect myself. To prepare.”

He focuses his attention and gathers his thoughts. He needs to have a singular focus: fix the problem, save the patient.

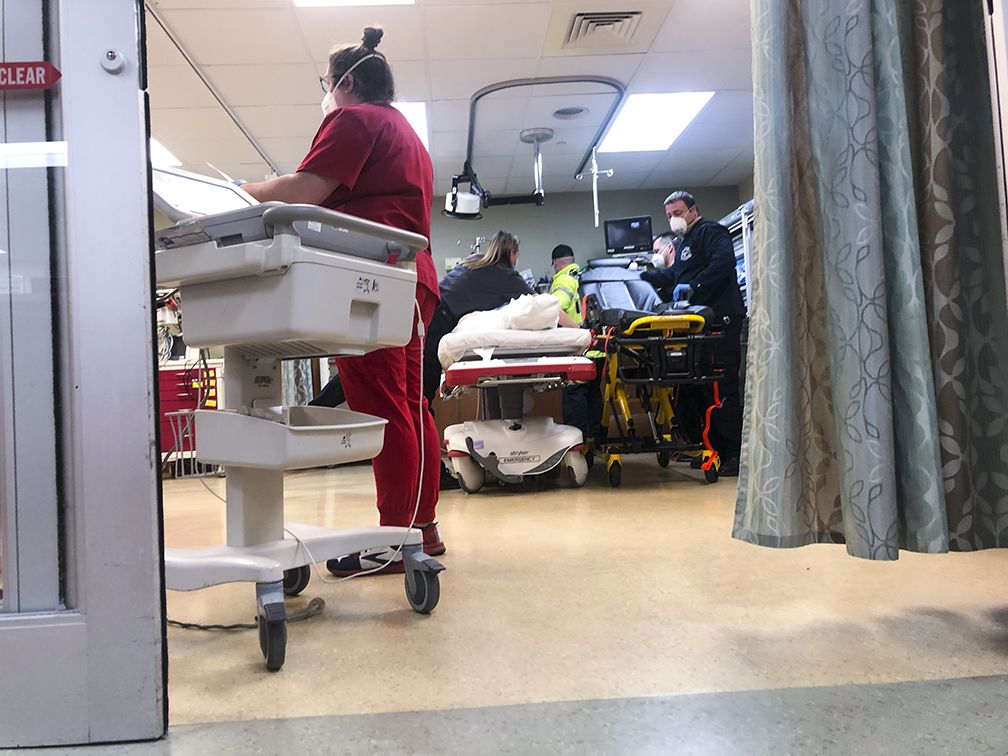

Arriving to the trauma bay, Dr. Lichter folds himself into the kinetic and coordinated energy of the trauma team gathering supplies. Dr. Marcus Romanello, the on-call emergency-medicine physician, organizes the nurses and respiratory therapy, and calls for air evacuation.

They see a man wheeled through the trauma-bay doors. He’s bleeding, clutching his chest. And they see why: he has a hole in it.

Move with intention

Trauma teams move at their own measured-in-seconds pace with dizzyingly calculated precision.

Trauma teams must think, decide, and move “with intention,” said Dr. Lichter.

“The point is to move, not to freeze. But to do so with precision without flailing. If you freeze, they die. If you overreact, they die. That’s my game plan in trauma.”

Many injuries that come to a trauma bay seem possible only in the movies. But there’s no Hollywood magic in a trauma bay—no special effects nor celebrities with trailers. Only real people facing the chaos of pain and those striving to bring order—and healing—to it.

And since 2019, Fort Hamilton Hospital’s level III trauma center has provided the area with lifesaving trauma care. But decades before he rounded floors and responded to traumas at Fort Hamilton Hospital, a young Dr. Lichter ate donuts in the doctors’ lounge.

Donuts in the doctors’ lounge

At four years old, Andrew Lichter set his sights on two career paths: being a pirate and a surgeon. Both promised adventure and larger-than-life problem-solving.

Growing up near Hamilton, he joined his father, Dr. Timothy Lichter, on countless trips to his office in Fairfield or to Fort Hamilton Hospital. As his father did rounds, Andrew watched old westerns and snacked on donuts, dreaming of when he, too, might save lives like “Doc” from Gunsmoke. During those formative years, he also witnessed his father’s approach to patient care, a combination of neighborly compassion and confident expertise that cultivated a visible trust Andrew saw between his father and his father’s patients, whether they were at the office or at the grocery store.

After completing medical school at the Toledo College of Medicine and residency at Wright State University, Dr. Andrew Lichter returned to his hometown to join the accomplished and growing surgical team at Fort Hamilton Hospital in June 2020.

Standing in the trauma bay years after eating donuts in the doctor’s lounge, Dr. Lichter knows he’s where he needs to be.

“Throw me that”

The team moves the patient to a trauma-bay bed. Bullet wounds riddle his body. But the most significant is the one that cut a hole through his heart.

Between breaths, he tells Dr. Lichter he’s dying.

A chest X-ray reveals blood has pooled around his heart, suffocating it. His blood pressure plummets, and he collapses into the bed.

Dr. Edward Brewer, an anesthesiologist with 30-years’ experience, intubates the patient. Dr. Romanello moves from the patient’s head to join as the first assist. And Dr. Lichter begins to open the patient’s chest.

“As he fell back, I already had my knife and supplies ready,” said Dr. Lichter.

He opens the chest, removes the blood, and finds the hole in the patient’s stilled heart.

Dr. Lichter asks for sutures—surgical thread for stitches—to sew the hole. But they aren’t available.

He needs to solve two problems at once: seal the hole and fill the heart.

That’s when he sees a urinary catheter (a foley) and calls to a nurse: “Throw me that.”

Dr. Lichter knows the foley gives him two things he needs to make the most of this last-ditch effort: a small balloon to fill the hole in the patient’s heart. And a narrow tube to help fill the patient’s heart with blood.

“It was the only thing I had available,” said Dr. Lichter. “And it provided me with rapid vascular access.”

“And it worked.”

40 minutes and 5 percent

The maneuver wins the team the minute they need to run a central line beneath the patient’s collar bone. And the nurses begin to diffuse blood into the patient.

The patient’s heart fills. Dr. Lichter squeezes it. And, for the first time in four minutes, it beats.

“The most amazing thing about the heart is that when you fill it with blood, it stretches the muscle, and it takes over.”

The patient’s other wounds needed to be addressed. Having cared for his life-threatening injuries, they move the patient to a helicopter waiting to take him to another facility for emergency care.

The patient had been in the trauma bay for 40 minutes.

“We were fast,” said Dr. Lichter.

And the team’s expertise matched their speed. The patient left the hospital, his heart beating again, among the five percent who leave after this severe of a wound.

The ones who won’t stop

A unique kind of collision occurs in trauma bays like those at Fort Hamilton Hospital. It’s a collision between the chaos of some of life’s worst moments and the commitment of some of the world’s most caring people.

The medical staff—the surgeons, nurses, and others—who comprise a trauma team willingly step in to fill a dramatic gap “where the number of minutes until a patient receives proper care,” said Trauma Medical Director Dr. Ryan Grote, “could mean the difference between life and death.”

Leaving the trauma bay, the patient on his way to receive further care, Dr. Lichter turns toward the stairs to respond to his next call: a patient with appendicitis. He responds to three more calls that day. In his words, “it was a busy day.”

And it’s the sort of day he and others serving at Fort Hamilton Hospital show up for every day—including Sundays.

“Our trauma team is amazing. We’re passionate about what we do and the people who live here,” said. Dr. Lichter. “If you come in, we will never stop caring for you. Ever.”