COVID units throughout Kettering Health work tirelessly to care for patients during another surge. As frontline workers face new (and familiar) challenges, they give their all to push against an unforgiving pandemic.

The COVID unit on the third floor of Kettering Medical Center pulses with quiet, focused activity.

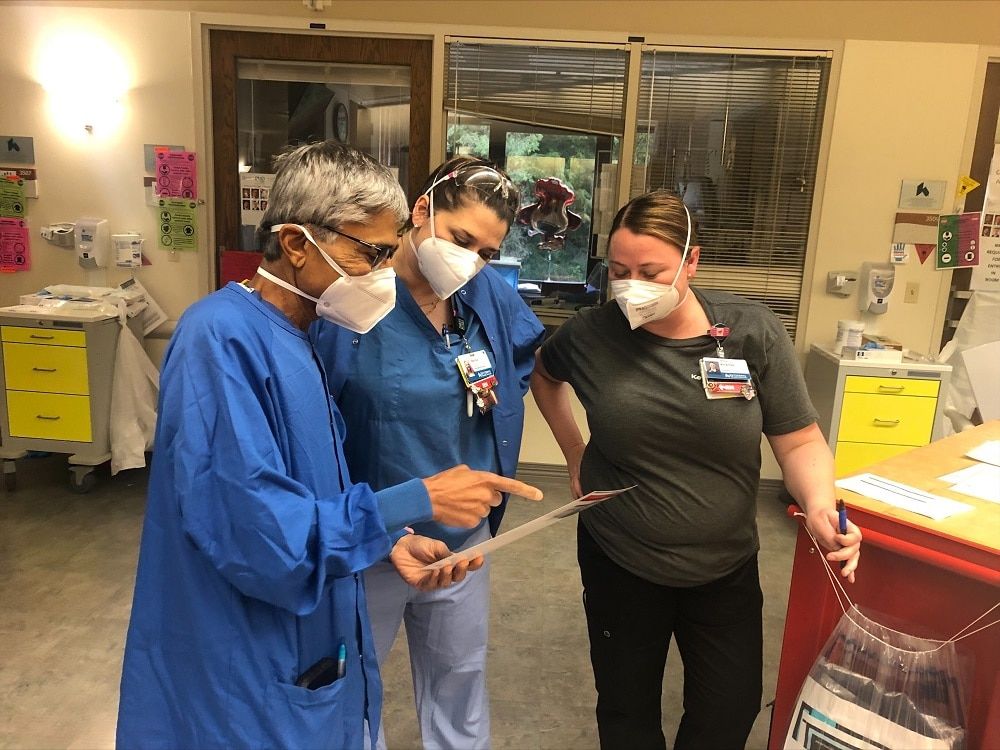

Muffled conversations, spoken through N95 masks, bounce between nurses and physicians. Everyone moves in calculated harmony: checking charts, scanning screens, and reviewing results. One thing is clear: they’ve done this before.

Past the nurses station, where the fluorescent lighting softens, are the patient rooms. Each room has someone the nurses know by name, someone they’re fighting for, someone they’re helping fight for every breath COVID tries to take.

In one of the rooms, a ventilator runs rhythmically, filling the lungs of a senior in high school.

In the nurses’ lounge, a few ICU nurses find a minute to eat a late lunch. It’s almost 3 p.m. Some stand and eat, momentarily moving their masks to fit small bites of pizza, maintaining a ready stance.

Another nurse walks in. A patient has spiked a fever and is losing blood pressure. And half-eaten pizza slices are left behind as the room nearly empties.

The remaining nurse tries to have a quiet moment to herself but interrupts her self-imposed silence to turn and say, “We have some really young ones here, you know, who are doing really poorly. Our spirits, I think, are low.”

Becoming a COVID unit (again)

Wearing blue scrubs and neon green running shoes, Dr. Hemant Shah walks into the lounge. He’s just come from the fifth floor where he and a chaplain held a “care for the caregiver meeting” for worn-thin ICU nurses.

He sits at the far end of the small table covered in half-eaten lunches, keeping his phone on his lap.

Dr. Shah, medical director of the ICU at Kettering Medical Center, knows well the rigors of COVID’s frontline. He, like many others, has served in the COVID units every weekend for the past four weeks. His eye contact is precise, his smile welcoming, and his tone impassioned and clear.

Motioning toward the nursing staff, he says, “We’re tired. But we have a good team. That’s what keeps us going.”

Ensuring they reinforce each other’s perseverance and stamina is as essential for their emotional health as wearing their PPE gear is for their physical health.

For Dr. Shah and the nursing staff, this surge evokes some of the terrible, familiar sights and sounds of the pandemic. But the combination of patients who are unvaccinated and the highly contagious delta variant has led to some stark differences in this COVID unit.

The first (of many) being the sharp shift from the public’s support of frontline workers to mistrust, if not skepticism and, in some cases, confrontation.

“The support is gone,” says. Dr. Shah. “We certainly don’t do this for a pat on the back. But it’s helpful to have some understanding.”

Fighting what could have been prevented

A physician for more than 27 years, Dr. Shah is no stranger to the complexities of caring for patients, patients’ families, and healthcare workers.

But even he feels the wear and tear from this surge.

“It’s extremely exhausting—for everyone. When you have to gasp for every breath for hours, for days on end, you can’t sleep. You can barely eat. We can see the exhaustion on these faces.”

While the severity of symptoms has frontline workers serving nonstop to care for patients, a distinct difference between this surge and last year lies in the fact that all this, says Dr. Shah, could have been—and can still somewhat be—prevented.

“Last year, we were exhausted, but we were resigned because there was nothing we could do,” he says. While the world waited in hope for a vaccine to become available to turn the tide against the pandemic, Dr. Shah and others did everything they could to care for patients and get as many home to their families.

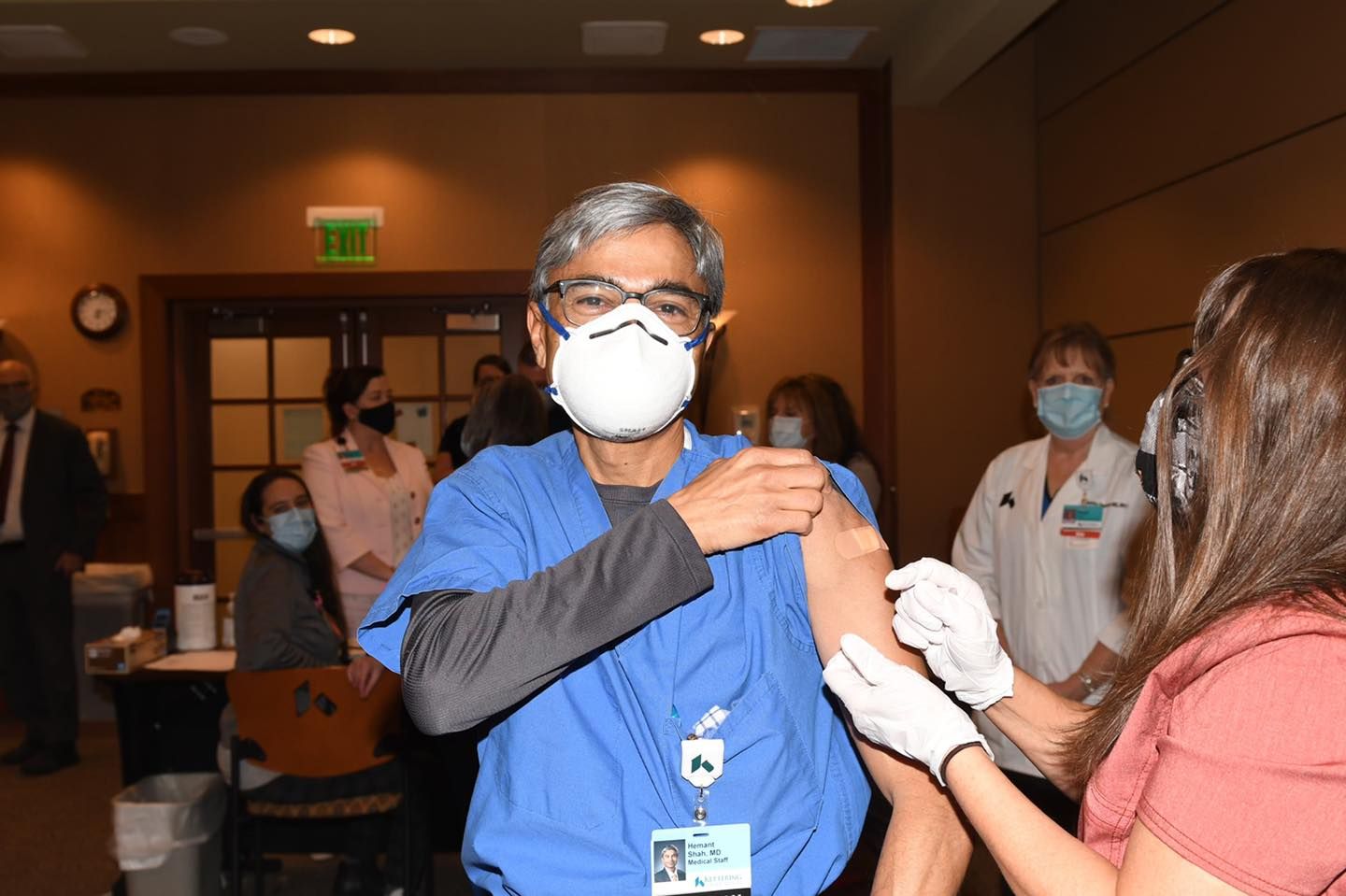

Then in late December 2020, the first COVID vaccines received emergency use authorization from the FDA. And the world began to move forward. On December 23, Dr. Shah received the first COVID vaccine given by Kettering Health.

And while significant progress has been made to try to elevate the public’s health beyond the reach of COVID, this recent surge has shown that things are far from over.

“This time, we’re exhausted but frustrated,” says Dr. Shah.

“There’s a solution that is available, is safe, and is effective. And when folks choose not to take it, it affects everyone else.”

Like patients who don’t have COVID but still need life-saving care for a heart attack or stroke. As cases of COVID climb, Dr. Shah says, “It’s a challenge to find beds.”

This cascade of COVID’s complications makes for long days for healthcare workers like Dr. Shah. But what keeps him and others awake at night is not just that most of the patients in the COVID units are unvaccinated.

It’s that some patients fight to breathe in the COVID unit when they should be cheering at a Friday night football game.

“We’re seeing patients who could be our sons.”

Dr. Shah, himself a father, has seen the dramatic change in the average age of a patient during this surge.

“Last year, we saw people who could be our parents. But this time, we’re seeing patients who could be our brothers, our sons, and our daughters—some of whom are pregnant. That breaks our hearts.”

Frontline workers learned to navigate the substantial mental and emotional strain from last year, watching COVID-19 hospitalize patients and change families forever. This year, they’re again serving under the weight of a similar mental and emotional strain, compounded by the difficulty of seeing COVID’s unapologetic toll on younger patients.

And for those serving on the ever-present frontlines of this pandemic, as Dr. Shah says, “this is what’s even more emotionally draining.”

And it’s a toll every frontline worker willingly pays—physicians, nurses, radiologists, respiratory therapists, environmental staff who clean and prepare patient rooms, and everyone in between. And still, they serve.

Many of the younger patients Dr. Shah sees who are unvaccinated, as young as 17 or 18 years old, when they’re hospitalized from COVID, remain in the hospital for longer and need a deeper level of care.

“It’s not fun struggling to breathe,” says Dr. Shah. And for those hospitalized with COVID, especially those who are unvaccinated, that becomes their new normal.

What can be easily forgotten is that these realities don’t stay isolated in the ICU after Dr. Shah and others leave either. As Dr. Shah shared, “When we’re here [in the COVID unit,] we stay focused on making them better.

“But when we’re staring at the ceiling at night, these things hit us.”

Fighting (again) for normal

Dr. Shah checks his phone. He stands to walk toward the door.

“We want this to be over,” says Dr. Shah. “We all want things to go back to normal.”

Before leaving the COVID unit, Dr. Shah checks in with a few of the nurses. He talks through a few treatment plans for patients. And then he makes his way into the hall. He checks his phone again and walks toward the stairwell.

The background on his phone is a picture of him with his daughter from a marathon he ran with her before the pandemic.

And for Dr. Shah and the others, that’s the normal they’re fighting for: a normal with more time with families, more races with runners, more concerts filled with fans, more schools busy with students.

A normal with less masks, less ventilators, and less COVID.