He buzzes into the parking lot in his little yellow Chevy. At 6:20 a.m., only a few frost-coated cars sit behind Kettering Health Behavioral Medical Center. He parks, turning off the oldies station. Standing takes a moment. His 85-year-old knees stay stiff in the December cold. But with a grunt, Don Lynch stands.

His legs bow as he walks to the back door. Decades of mopping, scrubbing, and bowling will do that.

“Mornin’,” he says to a nurse in the hall.

“Morning, Don,” she replies. “Staying warm?”

“What’s warm?” he asks through a gravely chuckle.

In his office, Don wakes up his computer and starts in on time cards, schedules, and emails. “Supervisor stuff,” he calls it.

He pokes at an email, locating each key before pressing it. “I had just figured out those electric typewriters when we got computers.” That was in the 1980s—well before email. “No computer helped me scrub a floor.”

He thumbs through sticky notes, calling a number to remember whose it is. Above his desk, among safety signs, hangs the Serenity Prayer.

He squints at the clock: 6:50 a.m. By 8:15 a.m., he’ll dust mop, then scrub, the hallways.

He has made a living—and lived a life—in these and other hallways throughout Kettering Health. Longer than anyone else.

In April, “if I make it,” it’ll be 59 years.

A new job and a new home

In 1955, the Village of Kettering graduated into a city. More than 20,000 people moved to the bustling suburb over the next five years, making it Ohio’s fasting-growing community.

Even so, the nearest emergency rooms were in downtown Dayton, or 30 minutes south in Middletown.

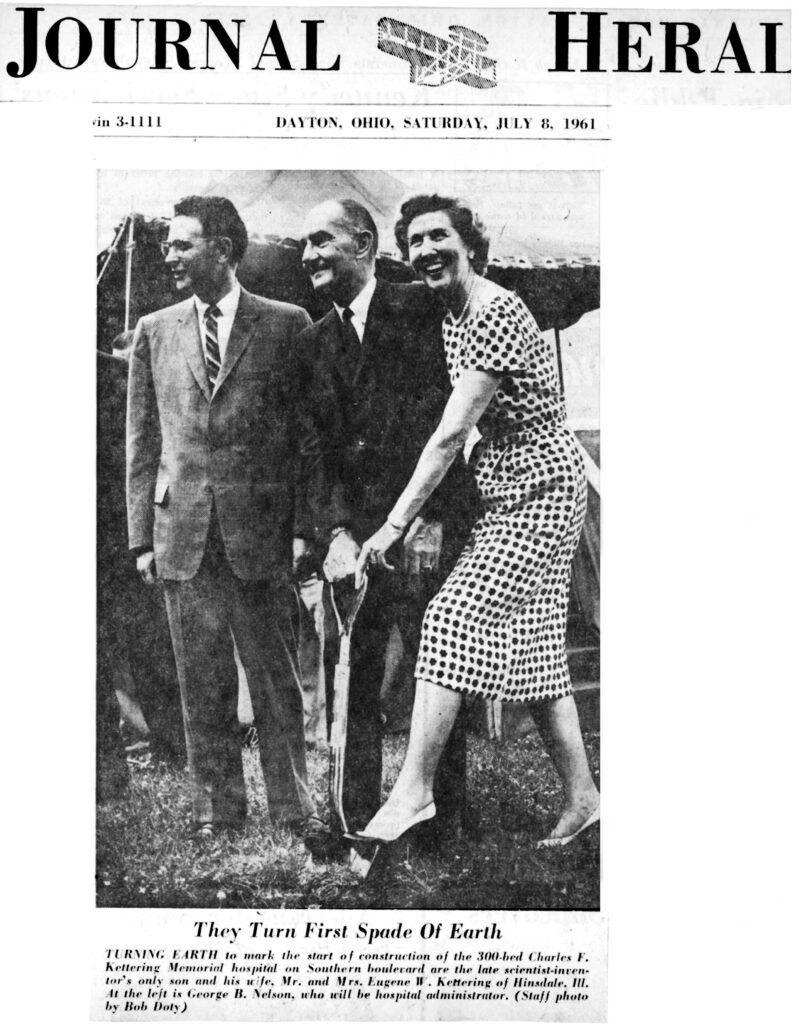

So when Eugene and Virginia Kettering broke ground in July 1961 for a new hospital, on land they donated, it signaled a new chapter for Kettering’s burgeoning community. On March 3, 1964, the Charles F. Kettering Memorial Hospital admitted its first patients. And five minutes away, at the Golden Nugget Pancake House, 25-year-old Don Lynch bussed tables.

His brother Richard, one of the cooks, got him the job that year. Before that, Don worked at Tip Top Restaurant in Chillicothe, Ohio—his hometown. He made $1 an hour, tossing salads, cooking steaks, and cleaning the front window during slow hours. “I probably cleaned it 50,000 times.”

Don arrived to Dayton looking for a new home. For himself, his late wife Shirley, and their kids. But he needed more money to move everyone. So, in the meantime, he stayed with his brother, rode the bus 80 miles every week to visit them, and he saved. And saved.

In April 1965, Don landed an interview at Kettering Memorial—with housekeeping. Richard, now working in the hospital cafeteria, helped him, again. Don wore his best shirt to the interview: a black-and-white striped polo. But the bus dropped him off late at his first stop near Carillon Park. Don then walked over three miles to the hospital.

The interview lasted 20 minutes, ending with Don being asked, “When can you start?” Don replied, “This afternoon.”

He was hired as a floor technician, responsible for the second floor. “The hospital was just a little box then,” he says, “compared to now.”

A quick study, he learned the tools of the trade (like the hand-held floor scrubber) and the methods (like the two-bucket protocol). He also learned that working at Kettering Memorial would be different.

“People were excited,” he recalls. “Everyone knew everyone, helped everyone. They made you feel at home.”

Don’s first boss, Jean Smotherman, learned Don traveled on weekends to visit his family. And how long he had saved. “She said, ‘Here, come on,’” and walked him to accounting. Don left with a no-interest loan to cover the rest. And paid it back in 10 months.

After a few years, he moved his family and could finally call Dayton, and Kettering Memorial, home.

Cleaning 500,000 square feet

The clock inches toward 7 a.m. as Don rolls around in his office chair, readying housekeeping carts. “It helps me avoid walking.”

The day crew—Barb and Lisa, “the girls”—arrive. The three swap stories then discuss the patient rooms that need cleaning before Barb and Lisa whisk the carts away. They head toward the rooms, a small but mighty convoy of cleanliness.

Don emerges from his chair, then walks out of his office into the smell of sneaker scuffs and basketballs. His office sits tucked in a corner room inside the medical center’s gym, opposite a closet with the floor scrubbers. His high-top Adidas squeak against the gym floor. “They’re not for style,” he says. “But support.”

His knees and the frost of gray hair may give away that Don is two months from turning 86. But not his schedule.

Wake up at 4:30 a.m. Drink a cup of Maxwell House and let Willie, his Shih Tzu, out. Get to work by 6:20 a.m. Leave by 3:30 p.m., then drive to his second job. Home by 7:30 or 8 p.m.—Monday through Thursday. And for a few hours on Sunday mornings.

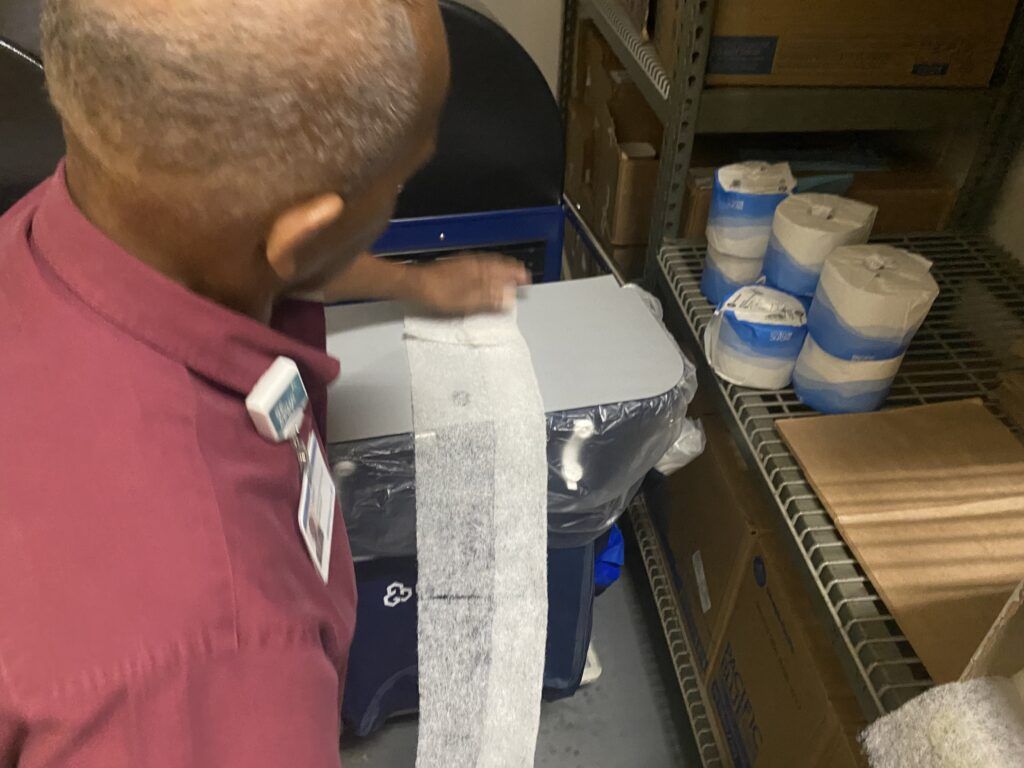

“I tried bowling in the work league this year. But that wore me out,” he jokes, opening the equipment room door. The smell of cleaner and metal escapes. He grabs his dust mop then unrolls a long, thin sticky cotton-like fabric. Don doesn’t measure it, knowing precisely where to tear.

He pats the fabric onto the mophead and waddles to the first of seven hallways. For the next hour, he pushes the dust mop up and down each hallway. Three passes each.

He greets staff and patients. But he doesn’t daydream. He just focuses “on the few feet in front of me.”

Those few feet have added up. Don guesses he has cleaned 500,000 square feet—more than eight football fields side-by-side. Chances are, it’s more than that.

Don admits to becoming something of a workaholic. But it’s work he likes, even loves. “You have to love your work,” he says, “to keep yourself going.” Especially since people walk on his, often unaware of the handiwork beneath their feet.

And therein lies the truth of Don: he cleans—not for audiences, accolades, nor applause. But to do it well.

Finding serenity

Don is the baby of his family. Born on February 3, 1939, he is the youngest of 15.

His dad, George, died when Don was six. His mom, Edith Mae, worked a little. She cleaned homes when she could. “I was best friends with my mom.”

Though a few older siblings had moved out, “we lived so poor.” Their home on a hill in Chillicothe had no electricity. No indoor plumbing. And an outdoor bathroom. During the winter, they used newspaper and cardboard to insulate the home. After they had electricity installed, they were given a Zenith radio. The box of wood and knobs towered over young Don, who loved the program The Shadow.

Growing up, Don wanted to join the military. Four of his brothers served in the armed forces. And in 1958, after graduating high school, Don enlisted—as the Vietnam War neared its third year. But not long after arriving at the base in Kentucky, he received a call; his mom was sick.

He returned to Chillicothe to help care for his mom and worked at Tip Top. In 1961, he married Shirley, and they had four children. Shirley died in 1986. Don later met his second wife, Patricia, who gave Don four more children, including his two stepsons. In 2008, Patricia died.

Today, Don has 22 grandchildren. He also has great-grandchildren but wrestles to remember how many.

He also wrestles at times with the growing number of goodbyes. Don is the last of his siblings; Mary Ellen, his youngest sister, passed away in November 2023. In 2020, he lost a daughter, Dawn. And in 2020, a son, Richard.

“In the past four years,” Don says, “Six people. It’s been kinda downbeat for me.”

He says two things help him: “cleaning floors” and the Serenity Prayer. He memorized the first line:

God, grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change,

the courage to change the things I can,

and the wisdom to know the difference.

The day is never over

At 9:30 a.m., after a coffee and doughnut, Don returns to the gym to retrieve his humble steed, the SC1500 stand-on floor scrubber. The scrubber resembles Don a little: compact and built low to the ground. He steps on, turns the key, and the scrubber jolts to life.

“It sure was nice when they made these stand-on,” he says. “But even after all that standing, my knees still hurt.”

More people stir in the hallways as Don covers the length of one in 33 seconds. He makes two passes per hallway.

“Hello,” he says as he hums past patients and staff. Some staff step out of their offices to say “Hi, Don!”

“We love Don, absolutely love him,” says Julie Hall, a nursing supervisor. “He’s an institution.”

He finishes scrubbing by noon, cruising back to the gym to fill the scrubber with water for the night crew. Back in his office, he sinks into his chair. “Time to see if I missed anything,” he says, checking his email inbox. Empty. He then sifts through supplies, calling about an order that hasn’t arrived.

He yawns mid-sentence, rubs his eyes. Then looks at the clock. He waits until 1 p.m. to eat lunch, after everyone else eats. That way he can clean the tables and collect the garbage. That’ll take him to 2:30 p.m.

He’s leaving an hour early today, to visit Betty, his wife. She’s recovering from surgery. Then he’ll join his small cleaning crew at a nearby healthcare facility. For about 30 years, he has run “Don Cleaning,” his small cleaning business.

He started it after accumulating extra cleaning jobs. Most of his early clients came from conversations in the hallways at Kettering Memorial. Mostly doctors, occasionally administration. And one notable couple: Eugene and Virginia Kettering.

Learning from Mildred

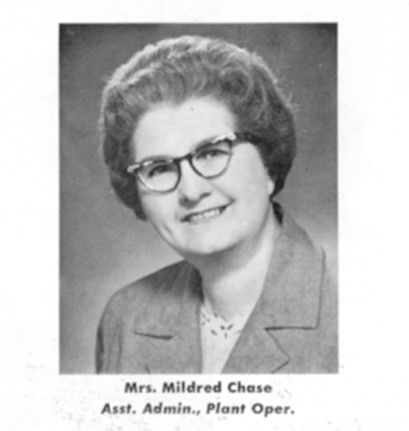

Virginia Kettering envisioned Kettering Memorial Hospital as a unique place of healing—down to the halls and walls. She entrusted that vision to one person: Mildred Chase, the hospital’s executive housekeeper.

“Mrs. Chase was at the top in her field,” says Judi Neff, author of Kettering Medical Center: Fifty years of caring and innovation, “and helped the hospital receive national recognition for its beautiful interiors and routines to keep it absolutely clean from top to bottom.” Mildred turned housekeeping into a science to learn, a discipline to apply. She wrote books like Introduction to the Theory of Institutional Housekeeping.

Don hasn’t read the book. He didn’t need to. Mildred “was a stern lady,” he says. “And she taught me everything I know about cleaning floors and keeping patients safe. And she wanted me to succeed.”

In 1967, Mildred promoted Don to floor supervisor. He oversaw the small floor team—responsible for the hospital’s five floors—and the stockroom. He was never one to stay at a desk, though. “I prefer to work with people,” he says. “Not around them.” He helped scrub the floors, collect trash, and clean windows, making Mrs. Kettering’s vision a reality in every possible square foot of the building.

And Don taught many others to see housekeeping the same way, including his summer interns. Like 15-year-old Michael Brendel, or “Brend” as Don calls him.

They both recall when Don first put a floor scrubber in Brendel’s hands, only to watch it careen across the floor into a wall. That was in 1974. Today, Brendel serves as president of Kettering Health Dayton and considers Don “a quiet and impactful leader to so many and a dear friend.”

Despite interest from other departments over the years, Don stayed in housekeeping, later called Environmental Services (EVS), where he watched the world change.

He remembers hearing sobs from the hall the evening Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated; watching the Challenger explosion; and reeling with others after the attacks of September 11, 2001.

By 2003, the five-floored hospital Don scrubbed nearly every square foot of had become part of a family of hospitals. And after 38 years at the renamed Kettering Medical Center (now Kettering Health Main Campus), Don began bouncing between facilities. In February 2014, he moved to the behavioral medical center, where he leads and cleans with the same focus he learned from Mildred.

What tomorrow may hold

The dining room tables are cleaned. The garbage emptied. And the floors scrubbed.

Don walks to the loading dock to check in with “the girls.” At 2:30 p.m., he puts on his jacket and jangles the pockets to make sure he has his keys.

On his way out, he walks past some nurses as one spots him.

“Don, you bowling on the team next year?” one asks.

“I don’t know, darlin’. That wore me out last year,” he says through a chuckle.

“We’ll keep you as an alternate then. How’s that?”

“Sounds good.”

As he exits into a blast of cold air, his knees ache. “My doctor told me it’s time to get them done,” he says. “I told him, ‘I’ll take them with me.’”

But retirement he might consider. He would like to get to April, making it 59 years, then travel with Betty. Germany. England. San Diego. But first, Hawaii. Of course, though, he’ll keep “Don’s Cleaning.”

Why? He doesn’t really know. Perhaps fear of idle time.

It’s certainly not fear of change. He’s acquainted with that. Kettering Memorial grew from one hospital to a 15-medical center health system—and Dayton’s second largest employer. Cars evolved from the mammoth ’49 Buick that hit him as a teenager—“It looked like it had teeth”—to the sleek self-driving shuttles he saw in science-fiction movies (He wants to drive a Tesla one day). Tip Top became a flower shop. The Golden Nugget closed. And “my bowling balls are gathering dust.”

But he’ll figure it out later. Tomorrow, he’ll be awake at 4:30 a.m. At work by 6:20 a.m. And focus on the few feet in front of him.