Cancer Care

Want to learn more about this at Kettering Health?

A New York City bus hisses, jolting Dr. Kristopher Marin awake. Yawning, he gets comfortable again on the pool float keeping him off the Staten Island sidewalk.

He’s been napping for about an hour, after arriving at 6 a.m.—the earliest he’s ever had to show up for a race. He tries to fall asleep again, shielded against early November’s cold by his pajama pants, a Dunkin’ beanie, and a bathrobe. But his mind races:

How’s this going to go?

Did I eat enough?

Did I train enough?

More buses ferry in neon-clad runners with tired eyes. Brooding anxiousness fills the street between the police barricades. The same thing is on all their minds: crossing the 2024 TCS New York City Marathon finish line.

By 8:30 a.m., Dr. Marin is on his feet—his Saucony Ride 14s to be exact. He tries to warm up among the cloistered runners. Some listen to music. Others nibble on bagels and bananas, killing time until 9:10.

Dr. Marin rehearses his race plan, shaking out his arms and legs, unaware of the buzzing in his fingers and feet.

The most bizarre start

Wearing bib number 8499, Dr. Marin waits spring-loaded for the start. Loudspeakers pour Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” over the runners packed in like sardines. He hates crowds. And this one is huge—the biggest in the race’s history.

He draws a long cold breath to counteract the adrenaline. And says a quick prayer. BOOM. A cannon fires, and the released wave of runners burst onto Verrazzano–Narrows Bridge.

Not many marathons start uphill. But this one does. The first two and a half miles are considered by some as the most demanding—at least mentally—of the entire race. But Dr. Marin smiles.

Bound for Brooklyn, he’s caught up in the movie-like moment: helicopters fly overhead; fire boats spray water in the bay below; runners shout and jostle for space; the sun bounces off his shades; and the world’s most famous skyline stretches from one end of the globe to the other. Of the races he’s run, this is “the most bizarre start to a marathon.”

He stays relaxed across the bridge. He’s not interested in setting a personal record. Across his orange jersey are the words American Neuromuscular Foundation, the charity he’s raised money for. Not only because he’s a physiatrist at Kettering Health Hamilton (caring for patients with nervous system, muscle, and skeletal conditions). But also because he lives with mild peripheral neuropathy—the buzzing in his body.

A side effect of the chemotherapy.

Not from Christmas cookies

Three years earlier, at Cincinnati’s Hungry Turkey race in November, he set a personal record in the half marathon: 1:26:43, or 6 minutes and 37 seconds per mile. “I was in the best shape of my life,” he shared, with more races planned.

But later that January, abdominal “bloaty feelings” started to annoy him. Holiday eating was the likely culprit, so he straightened out his diet. But after a few weeks, he still felt uncomfortable. An X-ray showed that he could be constipated. A simple fix with some over-the-counter medicine.

“Then I started noticing that I couldn’t run.”

On runs, his heart rate would skyrocket. Breathing became more difficult. For someone who’d run marathons for more than a decade, who ran after a tough day or when he was bored, this wasn’t from too many Christmas cookies.

Then Dr. Marin felt something in “the left lower quadrant” of his abdomen. Could it be a hernia? He reached out to Dr. Thomas Dunn, his primary care doctor, who saw him that day. He ordered a CT scan.

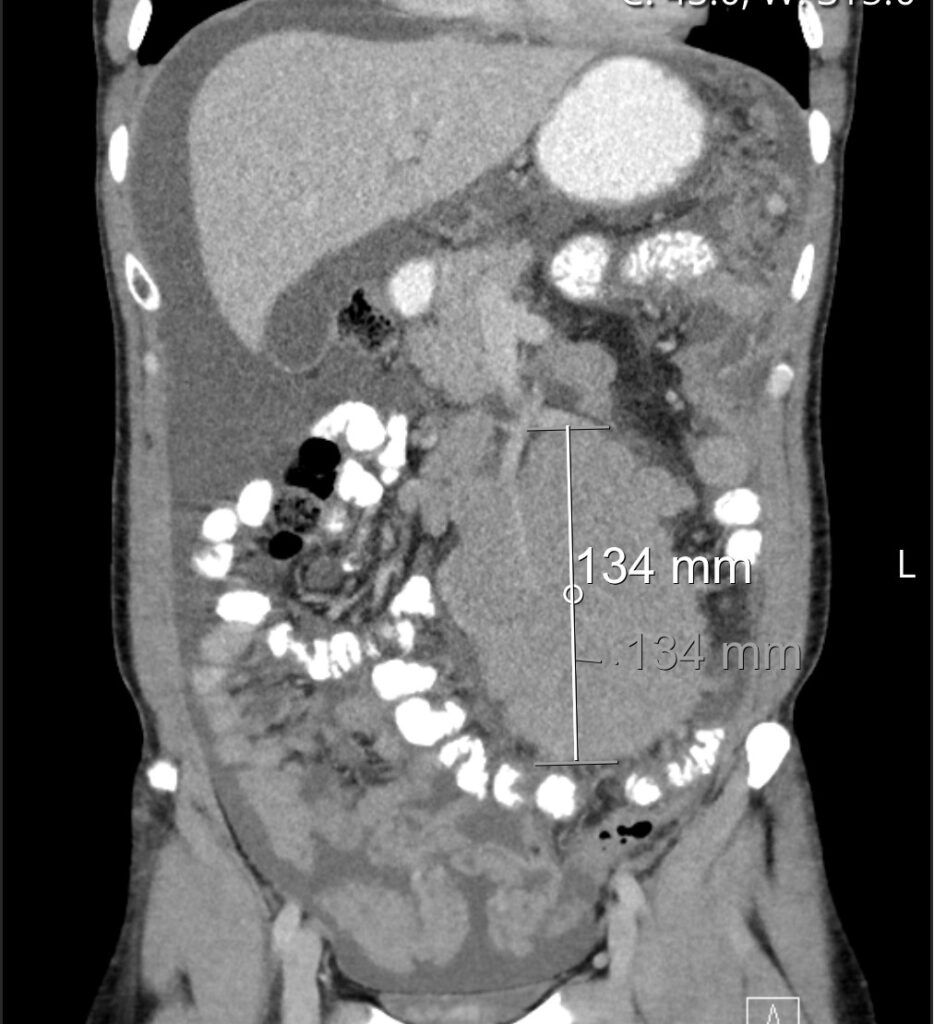

When the results pinged Dr. Marin’s MyChart, they showed fluid in his lungs. And a mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—around his intestines.

There was no definitive diagnosis yet. But he knew enough.

“My wife and I had a good cry.”

That night, Dr. Dunn called. He told Dr. Marin he’s setting him up with oncology. The next morning, Dr. Heather Riggs, oncologist, called.

Pain and bread

On the bridge, the only people Dr. Marin sees are runners. The only sounds he hears are runners’ feet against the pavement.

But as soon as he’s off the bridge, “It’s deafening. And the sidewalks are people-thick.”

Running under a helicopter hovering over the middle of the road, Dr. Marin reaches Brooklyn. He can barely hear the music in his headphones.

Cheering and clapping. High-fives and signs. Drumlines and bands. A previous champion of the women’s division once called this marathon, “The best block party in the world, but one of the hardest marathons you’ll ever run.”

The first New York City Marathon, in 1970, had 127 runners, with 55 finishing. Today, Dr. Marin runs through New York City’s five boroughs among more than 56,000 runners

Five miles in, he cruises at below seven minutes per mile. With no warning signs of tightness, indigestion, or any of the problems that bring runners to a stop.

He gives high-fives to spectators and sees a “Hit This to Power Up” cardboard sign with a Super Mario Bros. mushroom. Dr. Marin’s favorite sign says, “Pain Is Just French for ‘Bread’!”

A different marathon

On the phone, Dr. Riggs gave the mass a name. “This looks like lymphoma.”

Follicular lymphoma, a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It grows slowly in the lymphatic system—a crucial part of the body’s immune system, stretching across the body’s organs, vessels, and tissues. The average age of the 3.5 adults diagnosed each year with this cancer is 50 years old. Dr. Marin was 39.

Dr. Riggs listed a regimen of scans and treatments and timeframes, almost mimicking a marathon-training plan. This would be its own kind of marathon. Her no-nonsense, precise tone assured Dr. Marin.

“I’ll see you next week,” she ended.

“He was very, very ill from the effects of his lymphoma,” shared Dr. Riggs.

The pressure in his chest and abdomen worsened, interrupting more than just his running.

“I couldn’t even sleep lying down,” Dr. Marin said. “I had to try to sleep sitting up.”

Dr. Riggs ordered more CT scans to take a closer look at his lungs.

“And I found out why I couldn’t run,” he said. “I had a lot of pleural effusions—fluid filling the lining of my lungs.” Same in his abdomen, too. Additional scans showed cancer growing in the lining of his heart, lungs, and even around his collar bone.

To give him some relief, he had two procedures to remove the fluid. “But then the fluid in my lungs came back.” During a follow-up procedure, they removed a liter and a half.

Chemotherapy, then immunotherapy, would follow. With the pressure in his chest relieved, Dr. Marin asked Dr. Riggs, “When can I start running?”

Despite their capacity for endurance, runners aren’t the best with waiting.

Not long after having the fluid removed, Dr. Marin plodded off from his house—shuffling a mile out, then back.

It didn’t go well.

Central Park

Snaking his way through the Bronx, Dr. Marin floats through the next few miles. He cruises into a water station bottlenecked with runners, slowing his pace just enough to grab a cup and return to the race. His shoes now covered in stains from puddles of sports drink and layers of green cups that collected on the street.

As a kid, he didn’t know people did this—running just to run. Until he learned he had a knack for it.

In high school, he tried out for the track team, learning after some trial and error that the longer the distance, the better it went.

“They put me in the 400-meter dash. Hated it. Put me in the 800 meters. Hated it. Put me in the mile, and I thought This is a little better. Then I ran the two mile and was like, ‘OK, now we’re talking.’”

It wasn’t until his first year in medical school that he ran his first marathon. He finished in 3 hours and 54 minutes. In the 13 years between then and New York City, he’s run more than 10 marathons and half marathons.

Thundering forward, he makes way toward Central Park. With its autumnal splashes of reds and oranges, the park is deceptively serene. If the first bridge is the most mentally daunting, Central Park is the most physically brutal. From his online race research, where he found the tip to bring the pool float, Dr. Marin knows the final miles are uphill.

As he enters the park, his legs grow tight. Lactic acid pools. He pumps his arms to keep his legs churning. And his lungs feel on fire.

Feeling tired, feeling lost

Chemotherapy affects every patient differently. But most feel some sort of nausea or fatigue.

Shuffling along the Indianapolis Motor Speedway racetrack in May 2022, Dr. Marin feels the fatigue down to his toes. He’d signed up for the OneAmerica 500 Festival Mini-Marathon, or the “Indy Mini,” well before Dr. Riggs’s phone call. Unaware of any cancer.

He felt decent after his initial treatments. He even managed to run a 10-mile race a few weeks before the half marathon, which went “OK.” But before the race, “the treatments started to knock me down.” He’d lost his hair. He dragged himself to work. And without running, he was lost. Normally, running would be his go-to escape. But he couldn’t escape his own body.

He was dying to run.

Dr. Riggs connected him with Maple Tree Care Alliance, a non-profit specializing in exercise oncology who partners with Kettering Health. “They really helped me understand what I can and can’t do,” said Dr. Marin.

He decided to try the half marathon.

After three miles into the Indy Mini, the fatigue nipped at his heels and psyche. He reached the finish alternating between running and walking for the last five miles. But he finished.

The cancer soon began to respond to the treatment. After six rounds of chemo, he shifted to maintenance treatments.

As his strength improved, Dr. Marin scheduled more races.

In May 2023, he returned to the Motor Speedway for a second Indy Mini. He never walked, finishing in 1:29:55, or 6 minutes and 52 seconds per mile. And gave his finisher’s medal to Dr. Riggs.

“She got me back,” Dr. Marin shared. “She’s been awesome—on top of it from the get-go. I wouldn’t be running if it wasn’t for her.”

No finish line

In Central Park, Dr. Marin runs past others who’ve slowed to a walk.

The final stretch brings runners outside the famous park into an expanse of Manhattan high rises that block the sun. Which, today, keeps already exhausted runners from getting too hot. One final kindness from the city that has made this race the epicenter of life today.

He locks himself into a calculated frame of mind. Every breath, foot strike, and swing of the arms is part of a synchronized approach to waste no energy.

As he enters the park a final time, volunteers, cheering crowds, and flags of the 137 countries represented in the race line the street. Dr. Marin passes runners shouting, crying, and grimacing. Doing whatever they can just to reach the finish line.

He crosses the finish as the neon numbers read 3:03:05. A personal record.

Caught up in the moment again, he smiles.

The minutes after finishing are a blur. Runners receive their finisher’s medal, a poncho, and then it’s off to find their friends, families, or a place to lie down.

It’s fair to say the race went better than he planned. He raised more money than he thought he could ($4,305 of a hoped-for $3500), running faster than he thought he would on the second-hardest course he’s run.

But he’s not thinking about what he raised, or his time, or that he’s one of the world-record-breaking 55,000 finishers this year. It’s that he ran at all.

“The world makes sense to me when I run.”

Which has taken on new meaning since his marathon with cancer has no finish line. No cure.

After two years of maintenance treatments, in June 2024, Dr. Marin shifted to routine monitoring, where it’ll stay. Until his cancer comes back.

“My cancer is one of those that isn’t going to go away. The only thing you do for it is beat it into submission. But . . . I’m still here.”

Resting, finally

Dr. Marin hobbles two miles to the family meet-up area, where his wife, Leslie, and their three teenagers wait. Instead of trying to find him throughout the race, they were encouraged to go enjoy the city. Outside the park, he finds his family in their matching orange shirts.

Cheers echo above the city’s horn honks and sirens. And will continue until the race’s official cutoff at 10 p.m.

He asked a lot of his body the past three hours. Which explains the soreness and the pang of hunger deep in his abdomen. Tomorrow, going downstairs won’t be easy.

As they walk into the city, Leslie turns to him and says, “You need a pastry!” And leads him to a pastry shop nestled by an alley. There, he sits down, draped in his orange poncho.

And his marathon ends with bread.