The most bizarre start

Not from Christmas cookies

Three years earlier, at Cincinnati’s Hungry Turkey race in November, he set a personal record in the half marathon: 1:26:43, or 6 minutes and 37 seconds per mile. “I was in the best shape of my life,” he shared, with more races planned.

But later that January, abdominal “bloaty feelings” started to annoy him. Holiday eating was the likely culprit, so he straightened out his diet. But after a few weeks, he still felt uncomfortable. An X-ray showed that he could be constipated. A simple fix with some over-the-counter medicine.

“Then I started noticing that I couldn’t run.”

On runs, his heart rate would skyrocket. Breathing became more difficult. For someone who’d run marathons for more than a decade, who ran after a tough day or when he was bored, this wasn’t from too many Christmas cookies.

Then Dr. Marin felt something in “the left lower quadrant” of his abdomen. Could it be a hernia? He reached out to Dr. Thomas Dunn, his primary care doctor, who saw him that day. He ordered a CT scan.

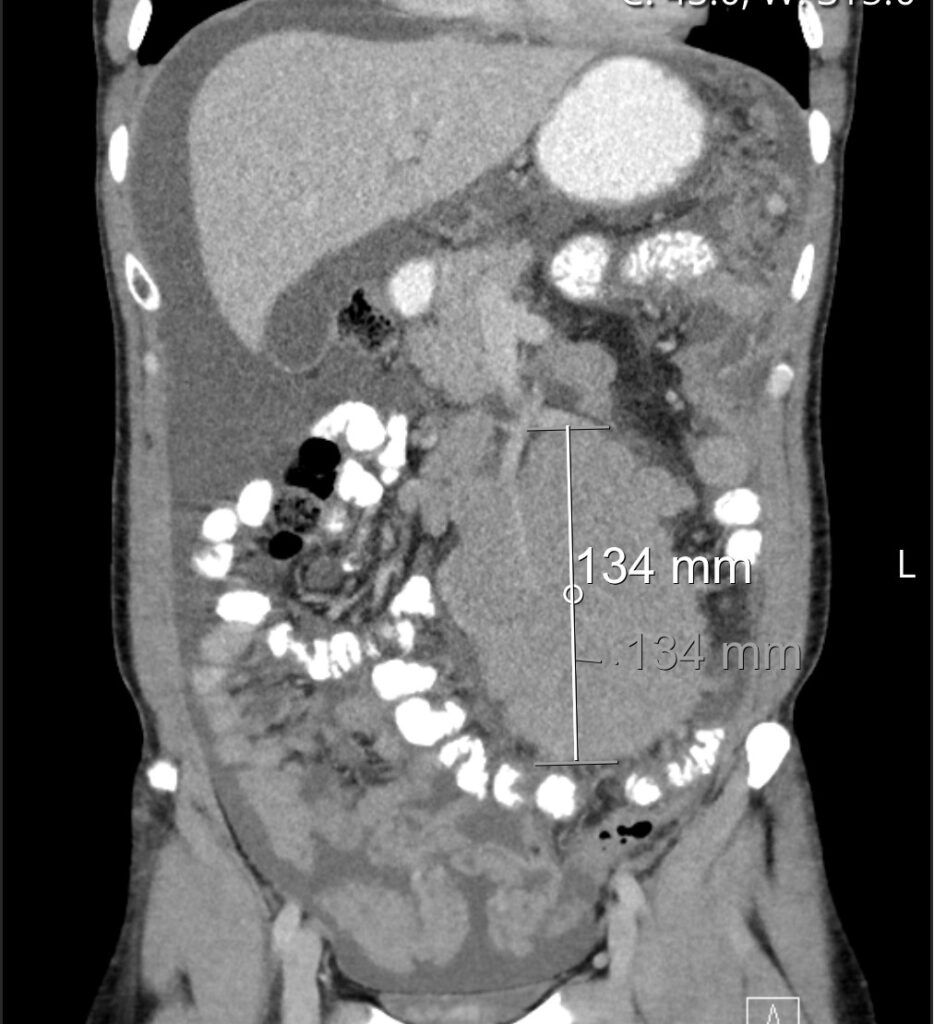

When the results pinged Dr. Marin’s MyChart, they showed fluid in his lungs. And a mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—around his intestines.

There was no definitive diagnosis yet. But he knew enough.

“My wife and I had a good cry.”

That night, Dr. Dunn called. He told Dr. Marin he’s setting him up with oncology. The next morning, Dr. Heather Riggs, oncologist, called.

Pain and bread

A different marathon

Chemotherapy, then immunotherapy, would follow. With the pressure in his chest relieved, Dr. Marin asked Dr. Riggs, “When can I start running?”

Central Park

Feeling tired, feeling lost

Chemotherapy affects every patient differently. But most feel some sort of nausea or fatigue.

Shuffling along the Indianapolis Motor Speedway racetrack in May 2022, Dr. Marin feels the fatigue down to his toes. He’d signed up for the OneAmerica 500 Festival Mini-Marathon, or the “Indy Mini,” well before Dr. Riggs’s phone call. Unaware of any cancer.

He felt decent after his initial treatments. He even managed to run a 10-mile race a few weeks before the half marathon, which went “OK.” But before the race, “the treatments started to knock me down.” He’d lost his hair. He dragged himself to work. And without running, he was lost. Normally, running would be his go-to escape. But he couldn’t escape his own body.

He was dying to run.

Dr. Riggs connected him with Maple Tree Care Alliance, a non-profit specializing in exercise oncology who partners with Kettering Health. “They really helped me understand what I can and can’t do,” said Dr. Marin.

He decided to try the half marathon.

After three miles into the Indy Mini, the fatigue nipped at his heels and psyche. He reached the finish alternating between running and walking for the last five miles. But he finished.

The cancer soon began to respond to the treatment. After six rounds of chemo, he shifted to maintenance treatments.

As his strength improved, Dr. Marin scheduled more races.

In May 2023, he returned to the Motor Speedway for a second Indy Mini. He never walked, finishing in 1:29:55, or 6 minutes and 52 seconds per mile. And gave his finisher’s medal to Dr. Riggs.

“She got me back,” Dr. Marin shared. “She’s been awesome—on top of it from the get-go. I wouldn’t be running if it wasn’t for her.”

No finish line

In Central Park, Dr. Marin runs past others who’ve slowed to a walk.

The final stretch brings runners outside the famous park into an expanse of Manhattan high rises that block the sun. Which, today, keeps already exhausted runners from getting too hot. One final kindness from the city that has made this race the epicenter of life today.

He locks himself into a calculated frame of mind. Every breath, foot strike, and swing of the arms is part of a synchronized approach to waste no energy.

As he enters the park a final time, volunteers, cheering crowds, and flags of the 137 countries represented in the race line the street. Dr. Marin passes runners shouting, crying, and grimacing. Doing whatever they can just to reach the finish line.

He crosses the finish as the neon numbers read 3:03:05. A personal record.

Caught up in the moment again, he smiles.

The minutes after finishing are a blur. Runners receive their finisher’s medal, a poncho, and then it’s off to find their friends, families, or a place to lie down.

It’s fair to say the race went better than he planned. He raised more money than he thought he could ($4,305 of a hoped-for $3500), running faster than he thought he would on the second-hardest course he’s run.

But he’s not thinking about what he raised, or his time, or that he’s one of the world-record-breaking 55,000 finishers this year. It’s that he ran at all.

“The world makes sense to me when I run.”

Which has taken on new meaning since his marathon with cancer has no finish line. No cure.

After two years of maintenance treatments, in June 2024, Dr. Marin shifted to routine monitoring, where it’ll stay. Until his cancer comes back.

“My cancer is one of those that isn’t going to go away. The only thing you do for it is beat it into submission. But . . . I’m still here.”

Resting, finally

Dr. Marin hobbles two miles to the family meet-up area, where his wife, Leslie, and their three teenagers wait. Instead of trying to find him throughout the race, they were encouraged to go enjoy the city. Outside the park, he finds his family in their matching orange shirts.

Cheers echo above the city’s horn honks and sirens. And will continue until the race’s official cutoff at 10 p.m.

He asked a lot of his body the past three hours. Which explains the soreness and the pang of hunger deep in his abdomen. Tomorrow, going downstairs won’t be easy.

As they walk into the city, Leslie turns to him and says, “You need a pastry!” And leads him to a pastry shop nestled by an alley. There, he sits down, draped in his orange poncho.